Christopher Rota, PhD

Scientist, Flow Cytometry

Welcome to this month’s installment of the Flow Matters blog! Generating good flow data starts with picking the right mixture of fluorescent labels to use in your flow cytometry assay (commonly referred to as a “panel”) and the right type of flow cytometer. When building flow assays, it helps to understand how flow cytometers read our mixtures of labels and produce the measurements that we spend so much time poring over during data analysis. In this post, we’re going to do a deeper dive into the technical side of how biomarker detection in flow works and the lessons it can teach us for practical assay design.

Somewhere Over the Rainbow – Biomarker Detection in Flow Cytometry

As we talked about in our very first blog post, flow cytometers operate on the principle that each label in a panel is attached to a fluorescent substance (also commonly referred to as a fluorochrome). These fluorochromes contain one or more fluorescent molecules (fluorophores), which can absorb light of a particular wavelength (color) from the cytometer’s lasers and emit light of another wavelength that can be captured by the cytometer’s detectors. The precise patterns of absorption and emission for each fluorochrome form its excitation and emission spectra: a distinct set of behaviors that form a recognizable signature in the measurements collected by our cytometer. The most important characteristics of this signature are the fluorochrome’s peak excitation and peak emission wavelengths: the points where it most strongly absorbs and emits light, respectively.

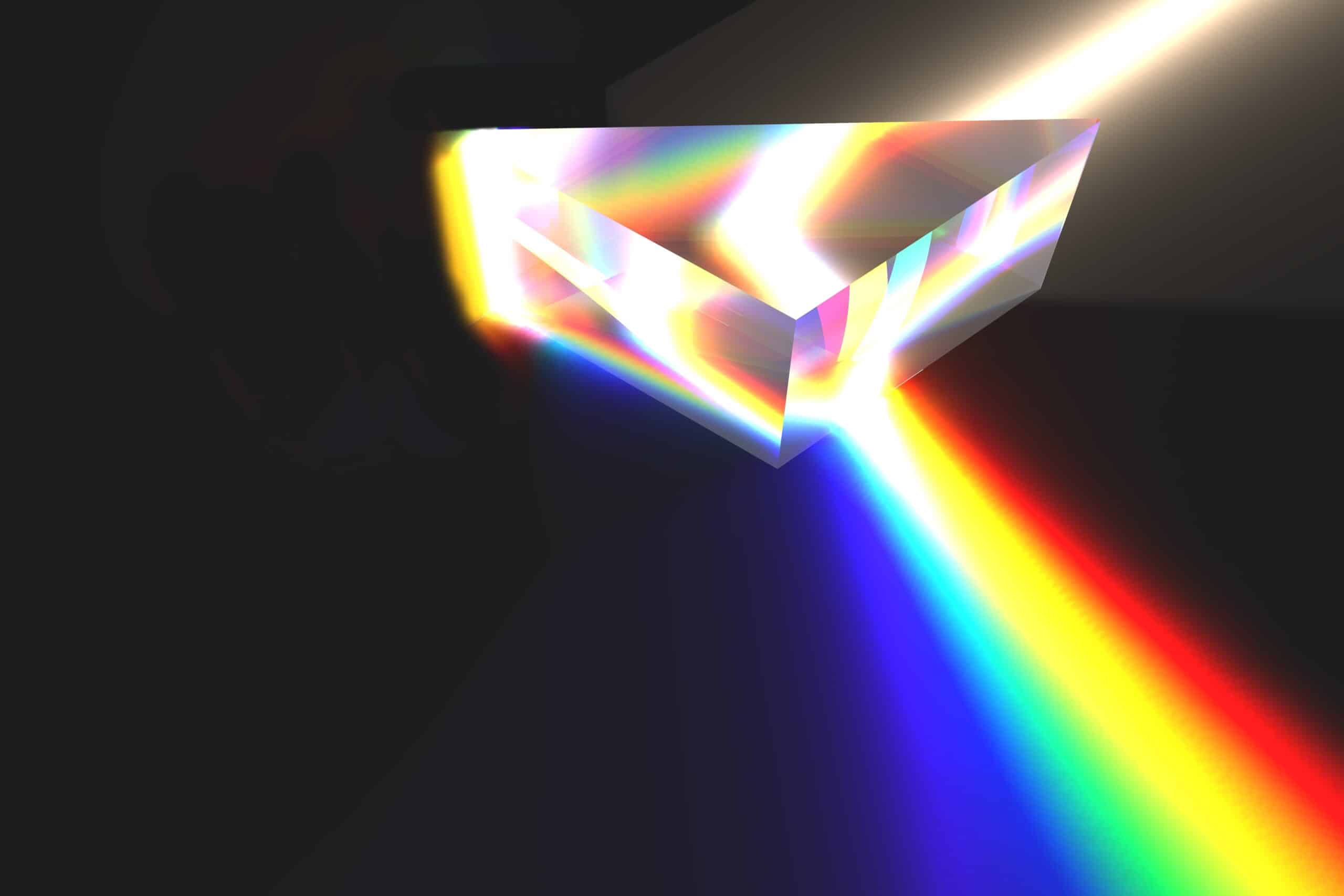

When picking reagents to use in a panel, it is important to use fluorochromes with as unique spectra as possible. By pairing markers to labels with distinct fluorescent signatures, we can more accurately trace the colors of light emitted by our sample back to their sources (our labels and biomarkers of interest). In a well-designed panel, a cytometer sees a cell like a human might see a rainbow: an array of carefully organized, unique colors that can be easily traced back to their origins.

With that image in mind, you might ask: how large of a rainbow (how many colors) can a cytometer accurately “see”? The answer: it depends on how the flow cytometer is constructed!

The first factor that influences a cytometer’s vision is how many lasers (different colors of excitation light) it is equipped with. The more lasers an instrument has, the more options you have to excite your fluorochromes with, and the better you can separate them based on that behavior.

As a simple example, let’s say we want to build a panel around two biomarkers: one marker for our cell type of interest (i.e CD3 for T cells) and one biomarker associated with the disease context we’re studying (i.e IL-17, an autoimmunity biomarker we discussed last time). We would expect both biomarkers to be found on the same cell at least some of the time, which means we need to pair them with highly distinct fluorochromes.

Two commonly used fluorochromes that could fit this bill are PE and APC. PE (phycoerythrin) can absorb light from blue or yellow-green lasers (reaching peak excitation at 565 nm) and emits a light red light (reaching peak emission at 578 nm). Allophycocyanin (APC) also absorbs yellow-green laser light but can uniquely absorb red laser light (peak excitation: 640 nm) and emits a darker red light (peak emission: 650 nm). If our instrument is equipped with both a yellow-green and a red laser, these two fluorochromes will be very straightforward to distinguish from one another. When we shine each laser on our cells in turn, we can be very confident that any signal we measure is coming from only our PE label or our APC label.

Using this same paradigm, we could expand our panel to include additional biomarkers using other distinctly excited fluorochromes, such as BV421 (best excited by violet laser light) and FITC (best excited by blue laser light). While there is some increased chance of misinterpretation for FITC, as PE also can be excited by blue light, we would expect the resolution of our two original biomarkers on PE and APC to be very similar between these 2 and 4 color panels. Success! We’re now collecting more information from our sample without any loss of accuracy – the dream scenario for any assay development scientist.

What happens if we want to add even more biomarkers, though? What do we do once we run out of lasers on our instrument?